|

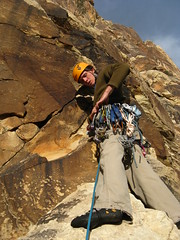

| "Jello" on the start of P2 |

When the day finished, I wondered what the crux really was. The past two days had been hard, and not just physically. I had pushed myself to my limit, just as I had three years ago when I climbed in Red Rocks for the first time. But back then, right before I arrived in Vegas, there was a glimmering thought that stopped me dead in my tracks. It blinded me when I stared directly at it, and I turned away because it seemed to be one of my dramatic intuitions that often turn out to be far less severe than they seem at first. But the thought lingered, and the more I thought about it the more it became a reality.

*****

|

| Reading the sequence before the disaster |

*****

Right from the start I was in doubt. I managed to link the first two pitches together slowly, but every move was an all-out effort that required complete focus and three or four heavy breaths. Time was not on our side and we knew that up front. I tried to be honest with both of us by stating that I was going to be slow. My calves ached from the previous two days and my body was sore all over. But even then I had questions about this route right from when he mentioned it. Epinephrine (5.9 IV) had always haunted me, even though I had never seen it in person. It was the mega-classic in Red Rocks, and it made sense that he'd want to get on this with his goals of doing longer and harder routes. I had only a feigning curiosity with it. It seemed like something I should want to do because it was a long moderate within my ability; it was a route that I should like because I like routes that take me away from the world for long periods of time, but there was always a thought that lingered in the back of my head that said, "Beware." I always assumed the warning was because of the physical nature of the climb; I just don't like vertical cracks that much, and I consider chimneys to be the widest of my least favorite style, but it was much more than that and I became dizzy trying to ignore what my heart was telling me: Give up.

*****

|

| Uh, yeah, this sucks |

"We've got to get to those descent cairns before it gets dark."

"I don't want to bivy."

"Damn this is hard."

"I'm sorry guys. I'm so, so sorry for being this slow."

The party ahead of us was barely visible once we started in the chimneys. The two parties below us had caught us at the start of the fourth pitch, and we had started with a two-pitch head start on them. By the time I hung for the seventh time in the second chimney, one party had passed us completely and the other patiently waited for me to clear the crux. That's right; they passed me in the chimney. I hung so many times at the crack that when I pulled over to the ledge the other party kept going. My fingertips were shredded and I had worn two large holes in one of my favorite climbing shirts. This was a full-body workout that I hadn't expected. I swore at "Jello" several times both in my head and aloud. I didn't want to be there. Questions started to seep into my head. The one that really caught me was an answer my mind hadn't expected but my heart had known all along.

*****

“You're doing fine.”

“It doesn't feel like it.”

“Don't worry. I think you're doing pretty well for a guy who's never been in a 5.9 chimney before.”

“I'm telling you, this doesn't feel right.”

The chimneys are wide in the most exposed sections. They're full-length chasms that drop straight down several hundred feet into the wash below. I think it would be much easier to climb the wider sections because one can extend the legs and keep the back stiff and straight, but alas, there's a problem with that: There's no gear out there. The pro is tucked in tight where the walls pinch down and, naturally, that's where the pressure is.

I didn't have a choice where to go because I wasn't leading, and in some ways this was an important part of what was bothering me. No, it wasn't that I wanted to lead the chimneys because I certainly did not. But I have been running away from exposure, and I started to see that while I thrashed my way up and hung several times in the narrow sections of the chimneys. And by exposure, I don't mean climbing. I had been staring at it since I first saw it three years ago. That glimmer, it was I looking into a mirror and wondering if I had what it took to give up those things that were most important to me in order to pursue something greater. And if I did have what it took, which one would I give up? I had two passions in life, but one was more a time filler, which could have been any activity if climbing hadn't captivated me at a moment when I had nothing to lose by being adventurous. Someone once told me in an Al-Anon meeting, "Alcoholism is all about timing. If you don't need that first drink when you take it, you'll probably never have a problem, but if you do need it..."

I needed it. I was away from home and alone for the first time in my life. That may not sound like much to everyone, but it is a lot to some and I had no clue what was out there in the world. Just stepping on the plane was a commitment, and stepping off felt as if I had let my limp body dangle in the air with only my chin keeping the rope from snapping my neck. I couldn't go home because I was five time zones away in another country. School wasn't fulfilling and I didn't have the money to live it up as an ex-pat playboy. Kevin and Mat took me climbing one rainy day in January an hour north of Edinburgh and I was hooked. Then Mat died a few years later in a rappelling accident. Kevin relayed the news, I told my now ex-wife, and then I went climbing.

“It doesn't feel like it.”

“Don't worry. I think you're doing pretty well for a guy who's never been in a 5.9 chimney before.”

“I'm telling you, this doesn't feel right.”

The chimneys are wide in the most exposed sections. They're full-length chasms that drop straight down several hundred feet into the wash below. I think it would be much easier to climb the wider sections because one can extend the legs and keep the back stiff and straight, but alas, there's a problem with that: There's no gear out there. The pro is tucked in tight where the walls pinch down and, naturally, that's where the pressure is.

I didn't have a choice where to go because I wasn't leading, and in some ways this was an important part of what was bothering me. No, it wasn't that I wanted to lead the chimneys because I certainly did not. But I have been running away from exposure, and I started to see that while I thrashed my way up and hung several times in the narrow sections of the chimneys. And by exposure, I don't mean climbing. I had been staring at it since I first saw it three years ago. That glimmer, it was I looking into a mirror and wondering if I had what it took to give up those things that were most important to me in order to pursue something greater. And if I did have what it took, which one would I give up? I had two passions in life, but one was more a time filler, which could have been any activity if climbing hadn't captivated me at a moment when I had nothing to lose by being adventurous. Someone once told me in an Al-Anon meeting, "Alcoholism is all about timing. If you don't need that first drink when you take it, you'll probably never have a problem, but if you do need it..."

I needed it. I was away from home and alone for the first time in my life. That may not sound like much to everyone, but it is a lot to some and I had no clue what was out there in the world. Just stepping on the plane was a commitment, and stepping off felt as if I had let my limp body dangle in the air with only my chin keeping the rope from snapping my neck. I couldn't go home because I was five time zones away in another country. School wasn't fulfilling and I didn't have the money to live it up as an ex-pat playboy. Kevin and Mat took me climbing one rainy day in January an hour north of Edinburgh and I was hooked. Then Mat died a few years later in a rappelling accident. Kevin relayed the news, I told my now ex-wife, and then I went climbing.

*****

|

| Can you see the fatigue? |

Our car was alone except for two vans that were camping in the lot. My water bladder was dry and all of our food had been eaten. I couldn't feel the middle two toes on my right foot; they were numbed solid. The once tall, brightly-lit pillars of Black Velvet Canyon were now one dense mass in the dark. In the daylight, they provided the shade, but at night they were the shadow and I wondered when they would sneak up behind me and take me prisoner again if I didn't keep an eye on them. Vegas was a blur of light off in the distance. If had the energy then I would have run toward the light. Was I ashamed of the murder I had just committed, or was it a mercy killing that had to be done?

*****

|

| "Jello" comes up where I almost let go |

“What are doing?”

“Aren't you tired? Didn't you say down below I might have to lead the rest of the way?”

“I feel better now. I should lead this pitch. This one is mine.”

“OK then. Hurry up and get going.”

“I am, don’t worry about me. I’ll do my job.”

I said my piece with the full authority of a rejuvenated body and soul. There was no one below us to slow me down, and I believed that would actually speed things up. All that talk at the bottom had just been a wimpy desperation. Everyone copes with difficulty differently, and I like to build my confidence by complaining a lot. It's as if complaining is a method of weeding out the bad stuff as a reminder that things aren't that bad when they're spoken. "It only gets bad when there's nothing to say," I thought to myself, "and I've been doing a lot of talking today."

The pitch breezed by in no time at all. The climbing felt easy, and I was enjoying the exposure of being on top. The blood was flowing through me again. My heart was thumping happy thoughts, and suddenly I didn’t want it end. I even risked a thirty-foot fall by staying out of a short crack and climbing an unprotected overhang instead, and when I rocked over it I told the crack to piss off and I gave it the bird just to show how pumped I was to have my confidence back. Then I ran up the rest of the pitch placing only a few pieces of gear here and there out of respect for the unknown. I didn’t really care much; I was fluid and smiling, and all of this seemed fun again.

But as I sat on top of the Elephant's Trunk, I relaxed. It was nice sitting there with little more to do than pull up the rope. I watched the red, white, and brown bands of sandstone wander up into the canyon where the wash pinches down to slabs and gullies, and I wiped my teary eyes from the wind that rushed back down past me on it's way toward Vegas. Every now and again I turned around to watch the climbers on Dream of Wild Turkeys (5.10a) and wondered why the wind was so much fiercer for them than it was for me on my much more exposed perch. I had been on that route two days before and couldn't wait to get off because I didn’t want my calves to suffer anymore from the hanging belays. I was glad I wasn't there at that moment. In fact, I was glad to be nowhere at that moment, so much so that when "Jello" finally made it to the top of the pitch, my body had molded itself so well into the seat that I didn’t want to go any further.

"Jello" gathered the gear and we switched the belay so he could lead. He racked up while I begged to remain where we were. I wanted more food, drink, rest, freedom. The energy that had grown inside of me on top of the Black Tower had now sapped out of me and floated away, probably by the strong canyon winds. I slouched in my seat and did everything I could to keep myself from falling asleep.

*****

|

| Feigned enthusiasm |

*****

So what is the difference between a passion that's done and a passion that's followed? The obvious answer is that one is actively pursued - people go out and get it - while the other pulls the person in as a black hole does to everything that gets too close. One is chosen while the other chooses. I chose climbing.

*****

My second-to-last lead was the toughest. The crack in the corner was thin and the face on both sides slick as glass. I held on with one hand, my fingers wrapped around the only jug that I could find in the corner, and I asked myself if I wanted to jump. The math didn't matter. I knew I was at least twenty feet above my last piece. And I wasn't sure how far above I was from my last good piece, but it didn't matter. To go up meant fighting love, while down meant admitting the truth: I was less of a climber at that moment, twelve pitches up at my limit and near the top, than I was when I ascended my first climb. That first climb was a 5.4 and no more than twenty feet tall, and it rained when I got to the top. A mud waterfall rushed over the lip and down my shirt and pants, soaking me to my toes. Mat believed I'd never go again, but he asked if I wanted to go to a gym anyway, and I said, "After lunch."

Dizziness confused me, however, and somehow I made it to the anchor. "Jello" met me there in less than ten minutes; it had taken me well over an hour. He pulled the remaining gear off my harness and raced up the next pitch. I shivered at what I remember was the worst belay stance on the route. When I got to the anchor, I looked up and was pissed to see another pitch, particularly one at the grade that I said I'd lead when we did our planning. He never pushed me to take it. Instead he simply asked. His goal wasn't to get me to do something I might not have been able to do; he wanted to get to the cairns before dark set in. If I didn't want to lead, then he would. I never took offense to him asking, but the question set fire to an orgy of lies and I snapped.

“Where's the gear?”

“There is no gear.”

“Just keep going?”

“Just keep going. Don't ever stop. Just get to the top and walk off.”

“Don't ever stop?”

“Never.”

I never wanted to kill climbing, but it had to happen. Writing is my other passion, except, unlike climbing, it has been burning inside of me since I learned to read. I always wondered about the stories my mom read to me as a kid. Who put them together? Why did they tell that story instead of this one? Where did the stories come from? My grandmother told me a few months ago, just after I quit my job to focus on becoming a writer, that she saved three stories I had "written" when I was five years old. She was a businesswoman with an eye for technology and owned the first Apple personal computer that hit the market. I sat on her lap and relayed the stories to her while she typed. The printed versions were hidden in a box somewhere, but hadn't managed to find them until recently.

*****

"Jello" wanted to finish some business that we left behind on Dream of Wild Turkeys three days before. On that day we had done the direct start, which is The Gobbler (5.10a) and finished the rest of Wild Turkeys after that. He wanted to do the first three pitches so that he could say that we had done the route, but when we awoke the next morning we both realized it wasn't going to happen. He knew it was so because we were both tired and ready to go home. I knew it because I was done with that. Will I still climb? Yeah. Will I even push myself on climbs that are hard for me? Probably. But will I seek them out as if they are calling me? Not even if they beg, at least not until I've made it as a writer.

Click here for all 2010 Red Rocks photos.

|

| We made it. Tired, but true |

8 comments:

Nice write up.

Thanks John!

I found your blog via your post on rc.com. A fantastic write up of your epic on Epinephrine.

Thanks David for the kind words.

Fantastic trip report. Guess I'll have to add Epinephrine to my list.

You should post up more photos if you have them.

CRAP! I forgot to put the pics link on the bottom!!

Fixed!

Thanks Jon. Yeah, it's definitely a classic.

Hey Greg,

Nice write up. I can definitely feel you pain. You are not the first person to get totally rocked by Epinephrines first 4 real pitches. Those chimneys are killer full body workouts.

Well Eli, it's all your damn fault! I never would have even KNOWN about this climb had I not seen your photos of it!!!!

(just kidding of course)

Post a Comment