Nivea

Her eyes were as wide as a bucket of tears when I said I was going to be away that week.

“All week?”

“When do you leave?”

It was next Sunday, early, and Henry, Armando, and Catalina had planned to come home late that same day. Maybe I can come home early, I thought, and Henry confirmed that the hardest part was getting there:

“Getting back is a piece of cake, even if you don’t know Spanish that well.”

When we met to discuss our plan the Wednesday before we were to leave, I told Armando and Henry I would leave on Friday and that I hoped we would get to the top of the lower buttress before that.

“I understand,” Armando said. Henry did too. We had one week left together before she left to go home to Brasil. I was going to be away with them, and I wanted to see her one last time before she got on the plane. We had talked about me visiting in April, when her school year was slower after her students had settled in at the university where she taught, but this was also scary to us.

“Don’t have any expectations,” she said. “No plans.”

I deceived her and planned to return early just to see her.

La Montana

The first two arrived on Saturday with horses carrying their gear. I saw them in San Fabian and followed them along the dusty road to Don Jose’s farm where the long path begins. The bearded one, Armando, pulled the horse to base camp and then rode it back to the farm before walking the entire six kilometers uphill and across the knee-deep rivers back to the campsite. The girl, Catalina, was cooking dinner and I smelled protein in the air.

A red-headed climber, Henry, and a balded one, Greg, came two days later without horses. Their packs were too heavy and the terrain too steep and soft to continue, so after the first river crossing they left the climbing gear to tackle the steepest and softest terrain with only the food and camping gear in their packs. I felt they would not attack me until Wednesday now, so I prepared my defenses for then.

|

| The Team |

Greg

On Tuesday, Henry and I awoke late because on Monday we had awoken in Santiago at seven in the morning and had not fallen asleep at camp until after midnight.

“What do we do today Burnsie?” He asked.

“We rest,” I said.

|

| On the FA of Alabeo (V3) |

The hike back half-way to retrieve the climbing gear that we left at the first river crossing was easier than the day before, but it was still tiresome. We both wished that we had asked Don Jose for a horse. Next time, we thought collectively.

In the afternoon, Armando took us up a dry stream bed about ten minutes to a small overlook that offered a fantastic view of the cirque of walls around us. I was astounded at what I saw. None of it had been climbed, all of it a mix of grey, white, and red granite from the left in front of us at the start of the canyon to the right of us, into the cirque, and around to the back of us and back toward the entrance. We were surrounded by it, and it was loose, solid, and unclimbed. Excitement gave way to preparedness after the former had become the norm.

“Our objective is there,” he said pointing toward a coffin-shaped block before an obvious crack that led to the top of the first tower. “We will climb up the ramp that we cannot see here, but it is near the coffin, and turn right to the crack. The crack will get us to the top in maybe five or six pitches.”

“When do we start?” I asked. I was blessed they had invited me, but I couldn’t wait to get going.

“Tomorrow,” Armando said on Tuesday.

Armando

He had seen the cliffs four times from the plane to and from Patagonia. Finally he knew where it was and he searched on Google Maps to see exactly where. He showed the pictures to Henry and Henry showed them to Greg after Greg had arrived in Chile and after Henry and Armando had spent an entire day bushwhacking with a machete only to find that a path already existed. The path led to Don Jose’s farm, and he had made friends with the farmer so that on the return the easier path could be followed instead of the difficult one. On two trips, no climbing was done, only scouting, but he had found the line, and that was good enough for the future.

La Montana

|

| The first four pitches |

I was correct about them on Tuesday. Instead of coming to their line of attack, they played below me on my cannonballs that had rolled into the forest, and they also revealed another line of attack for another time that was much closer to camp. I was worried because the bald one wanted to climb me now there at the lower crags and my defenses were set up for deeper into the canyon, but I was lucky, too, that the bearded one had trekked all of his gear to the base of their chosen line the day before and he was without his harness and shoes.

“We can use my rack,” the bald one said. “And we have the bolts here at camp.”

“The drill and hammer are at the base of the climb,” the bearded one said. “And so are my shoes and harness.”

They left for camp, and I talked to the forest below and asked for some help. He asked for a lifetime of continued water to feed his trees and plants and I obliged.

“My runoff will always reach you,” I promised, and he agreed to keep them away.

El Bosque

The waiting was difficult. They said as they burned my dead the night before that they would leave camp early.

“It’s an hour-and-a-half at least,” the bearded one said.

But all four of them had slept in. The woman, the bearded one, and the redhead were stronger than the balded one, so I put the pressure on him when they finally attacked. The machete blazed a path through the thick brush I had put up overnight, but as they wandered along, the bald one lagged behind and I was able to quickly grow new bushes with sharp branches and thorns. The uneven ground that I had prepared worked to slow him, and thus the rest, too, down.

He fell a lot on the uneven ground, and his legs bled from the ankles to the knees and from the shin to the calf by the time they left me and entered the base of my friend La Montana. I watched them step into the sun and slowly work past the piles of rolling cannonballs to their line of attack. The bald one was weak indeed. It was possible I had slowed him enough to slow the rest down, too. It was now up to the mountain to defend.

|

| Top of P4 (end of the day) Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

The Team

We decided that Henry would lead the first pitch, and that Armando would come up second with Catalina and Greg following thereafter. Then it was Armando’s turn on the second pitch, and Greg would lead the third. Henry was shooting for the giant offwidth above us. It seemed the most protectable way to get us close to the giant crack that was now out of our view off to the right.

|

| Armando on the upper pitches Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

“Yes,” Armando said as we moved upward, “but the question is whether or not Greg climbs the corner to the roof, which is even closer to the crack, or if he traverses left to the offwidth.”

“It all depends on the gear,” Greg said.

As it was, the first pitch went easy, with all four of us climbing the 5.5 without incident. Armando’s pitch was harder, maybe 5.8, but it was difficult to tell because of all the vegetation that had grown in the crack. We tried to do some gardening, but the mountain was resisting, and the sharp edges of the stiff leaves cut us as we pulled past.

Greg’s pitch was the one where a decision was needed: follow the corner straight up or traverse left toward the offwidth. He wanted the corner to go, but after the start, which was the crux, there was no gear in the corner for about forty feet.

“It’s not worth it,” Armando said.

“Just get to the offwidth,” Henry advised.

He went left, traversing on easy terrain for thirty feet to a series of parallel cracks that brought him to the base of the offwidth.

Nivea

She wanted me to be safe and come home to her in one piece. I told her I would name a route after her. My pitch, which turned out to be 5.8R, with the runout section being much easier, was too ugly to name after her. I had seen another route instead, a curvaceous arch that flowed right before meeting a longer corner above that swayed back left, and it became my plan to return there to climb it and name it after her. But that wouldn’t be easy. Our goal was too long for the two days of climbing we had planned.

Still, I wanted to send her text messages all week to let her know how beautiful the canyon was and how much I missed her. Mostly I wanted to hear from her, too. Does she like camping? I wondered. This canyon was too beautiful to be saved only for climbing. Does she know I haven’t stopped thinking about her since I left her Sunday night?

Nivea was back in Santiago at the Spanish institute where we first met. Our mutual friends were fun people, and I was happy to think she was enjoying herself. She was working, too, because since she had met me she had completely disregarded her work for her university. In some ways this saddened me because she is happy to impact the world as a journalist and professor, but in other ways the trade-off meant I wouldn’t see her. I wanted to see her, and whether or not I made it to the top now was irrelevant. They had let me in, and I trusted them to let me stay there whether they made it to the top with or without me. She was leaving in less than a week. I wanted to climb, but I wanted to see her more.

|

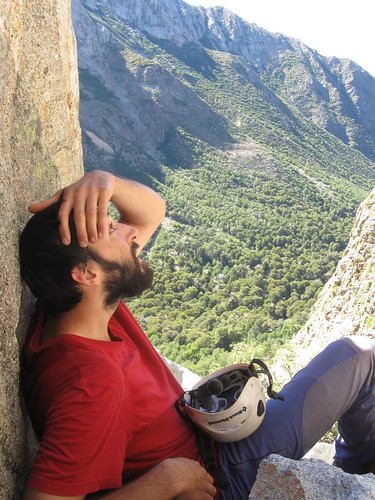

| A hard day Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

Greg

I was scared, and the team knew it. Loose rock made the opening moves tricky and committing. It took me about twenty minutes to clear the crux right off the anchor.

Then I saw the corner. I had wanted to climb this corner straight to the roof and by-pass the offwidth altogether, but when I got there, and even though I saw that the climbing was only about 5.7, I realized there was no gear.

“Can you clean the crack?” Armando asked.

“What good is that if it will take me ten hours to do it?”

“It’s your call Burnsie,” Henry said. “We can’t see what’s up there.”

This was my first ever first ascent attempt on lead. Never before had I gone up something like this. I was excited but very cautious. The long traverse left was easy and didn’t phase me, but the conglomerate rock, which was incredibly rare on this climb, at the end of the traverse worried me. If it crumbled when I weighted it then I was going for a long ride and swing back into the corner below the others, quite possibly back into the seemingly immovable sharp vegetation, too. A pierced lung or a sharp leaf through the neck didn’t seem that interesting to me, but I had no choice except to back down. Somehow I summonsed my courage and went for it, and it held.

At the anchor, Henry looked up at the offwidth and prepared to have fun.

La Montana

The bald one had not fallen into my trap of luring the team into the corner. My goal was to sucker them into the corner where it was harder to get to the crack on the right, even though it was closer. When they were to get to the top of the corner, near a roof that I had planted there to block their vision of the rest of the route, they were supposed to find that there was no gear to the left, the right, or above them, and that the traverse straight left to the wide crack they called an offwidth was going to be dangerous and scary.

I let it be easy for them, but they all saw that it would make things harder. The redhead wanted my wide crack since the start, and despite my disappointment they hadn’t gone straight up, I let him have it because I knew something he didn’t. He climbed me with great difficulty while the bearded one pounded more long, dull bars into my skin below and the woman took pictures. They had proof now that they were making progress, and I could sense that they felt they were winning the battle, but I knew. I knew I had more fight left in me.

|

| The Valley Photo by Armando Montero |

Armando

It took him a long time to set the rappel anchor. Clank! Clank! Clank! This was hard granite and he was getting tired. Henry was also throwing loose blocks down from inside the offwidth. Armando had to continually swing out of the way to avoid getting killed.

Finally, Henry got to the top of the crack, and as he went above it he saw that there was nowhere to go. He and Armando discussed in Spanish what to do. Four pitches in one day didn’t seem enough, but at the same time it felt appropriate.

“Let’s figure it out when we get up there,” he said.

|

| A little downtime in the forest near camp Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

The Team

After Henry built the anchor, Catalina climbed the crack. Then when she finished, Greg cheated and hung all the way up. Armando jugged up last, and by this time we were ready to go back down, leaving three fixed ropes to cover all four pitches. The final anchor was a gear anchor. There was no need to leave bolts where the route might not continue. The question of where to go next stumped us, but that question was left for another day.

We returned to the base and exchanged gear. Now that we knew Greg was going back on Friday and that we didn’t need two full racks for the second attempt, we took Greg’s gear back to camp. Greg and Henry headed down the scree-field and boulder-field first, with Armando and Catalina bringing up the rear.

|

| One of the many nearby water holes |

La Montana

I watched them walk down my cannonballs and into the forest below. The bald one and redheaded one were first followed by the woman and bearded one. They had failed to reach me today, but they had left their ammunition splayed all over the battlefield and I knew they would return soon. When was a question I could not answer, as they had given no indication as to what their plans were. I put my faith in the forest. I needed an extra day to prepare.

El Bosque

The mountain had spoken to me, and I listened, but it was difficult at first. I focused again on the balded one, but he was quicker and much more agile the second time through with much less weight on his back. It became even more difficult when I realized that he and the redhead were better at finding their way back than they were at finding their way to the mountain. My roadblocks failed to keep them from the dry riverbed, and my suspicious water flow failed to keep them from refreshing themselves after a long walk without water. They knew exactly where they were going, too, thanks to a small, yellow device that the redhead kept checking to ensure they were on the right track.

The bearded one and the woman knew how to get back, but they were behind the first two, and I decided that if I couldn’t stop them physically that I would attack their separation instead. Again, at first this was difficult because the redhead and the bearded one kept in communication via shouts through the air, but I was able to build thicker trees that destroyed the acoustics and soon they were too far apart to hear each other.

|

| Back at camp Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

Greg

Daylight faded and the forest soon became dark. We were out of earshot now with Armando and Catalina, but Henry felt OK that they were safe on their own. Armando had made this walk several times before now, so we felt fine continuing without them.

“Besides,” I said, “since we’re sharing cookware, it makes sense that we get there first and cook and eat before they arrive. That way no one has to wait to eat.”

We reached a water stop, the last place we truly recognized in the daylight, and headed back where we thought the path went. Cairns dotted the easy landscape, but that only lasted a while. Soon the air was darker than before, and sunset was officially past. The easy terrain had faded and we were bushwhacking again. The sharp branches and thorns dug into my skins. Slippery bamboo shifted under my feet, and the uneven ground that I now could not see weakened my balance.

“The GPS says we’re off course by about twenty feet to the right.”

We went twenty feet to the left and found the path, but a hundred feet later we were bushwhacking again.

“How about now?”

“Forty feet too far to the left.”

So we went back to the right and never found the path again.

“We’re only three hundred meters away.”

“I don’t see the boulders.”

“Now we’re five hundred meters away.”

What? I was confused, but Henry apologized and said the GPS wasn’t giving the proper readings.

“We’re too slow,” he said. “It needs speed to be accurate.”

Slow we were, and blind, too. Now the darkness had set in completely. I looked up and saw stars. My headlamp needed new batteries and the beam was as weak as my patience. We had found the boulder field close to camp now, but where was the path? I felt we were going in circles...too far to the right...to far to the left...the brush is too thick, turn back...to far to the right, etc.

It had taken us two hours to get to the base and we, particularly me, were tired then. It had taken us less than an hour to get to the boulders, but now we were lost, the GPS be damned. Somehow the forest had risen up against us, and I was ready to quit and sleep there, in the bushes, that night with my pack still strapped to my back just to get it all over with.

“We’re almost there Burnsie,” Henry said.

“I think I’m bleeding,” I said.

He laughed. I wanted to quit. There would be no climbing for me on Thursday.

The Team

|

| Looking down at Greg's Pitch |

So there it was. The plan to climb four days had been diminished to one in those first four days. There were maybe two more days left after Thursday, and Greg would be gone for both of them. That would make the team quicker, but it was clear there would be no attempt at a second route. The first route was now even in doubt. The team was in uncharted territory.

Greg and Henry made it back to camp first, but Armando and Catalina were very close behind. In fact, Armando startled Greg when they both went to fill the water bottles at the same time. This was a relief to us. We knew no one was lost.

Nivea

The next day we awoke and rested around camp. The afternoon dinner was a large one with lots of wine and food passed around. No one was going anywhere that day. It was a rest day because that was all anyone could muster.

In the afternoon they took naps while I walked back to the first river crossing blazing a clear-as-day path that I could find alone on the way back on Friday. Getting back early was a top priority for me. She left early on Sunday morning and Saturday alone was not enough for me.

I bathed in the warmer water far from camp and wished that she was there with me to enjoy the waterfall and swimming hole.

We drank more in the evening, but I went to bed early so that I could be up at sunrise and walking back to Don Jose’s farm before the intense Chilean heat set in.

La Montana

I watched the bald one walk off at sunrise on Friday. They had not made a second attempt on Thursday, and for that I thanked the forest. But on Friday the bearded one and the redhead came up alone for the final push.

It was to my dismay that they learned quickly that the top of the offwidth offered nothing to their goal, so they went left and discovered a crack. Then they climbed that and discovered a new way to go. Then they scrambled, and then they found a final pitch to the top of the lower buttress.

I watched them pose at the top so they could save the memories forever. They were the first to get to me, but I had still won. You see, even though their nine pitches had netted them a route, they failed to get to the top of the second tower that was on top of the first one. I had won. They had lost.

|

| FOOD! Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

Nivea

|

| Firewood Photo by Armando Montero |

The hike back to Don Jose’s was easy, much easier than anticipated than the hike in. However, the hitchhike back to San Fabian was less of a success. I managed to hitch for only half of about the sixteen kilometers and instead was forced to walk in the blazing sun along the dusty road while Jehovah’s Witnesses stopped to convert me on the long walk back. Saturday is not enough, I kept saying to myself. I wanted more time with her.

The bus from San Fabian to the highway near San Carlos was easy enough, but the road from San Carlos to Santiago was five hours longer than it needed to be. While I had bathed in the cold stream everyday at camp, I hadn’t really bathed since early Monday morning, and I felt bad for the Chilean man sitting next to me.

Finally Santiago came into view and I was at home waiting to hear from Nivea. She told me that the institute where we had met was having a graduation party and that she would be to see me soon. I showered and ate, and I waited for her. Finally, the call came and I rushed to her house. She met me downstairs and I pulled her in close.

We kissed and held each other for a long time. Life for both me and her the past few years had been difficult, almost hopeless for me. I wanted write more, to climb more, to love, and to be loved. None had proven magical until Chile, until that week in San Fabian, and until that moment when I held her again in Santiago.

We were alone until the morning, and we were together all the next day on Saturday. Then were were together until she left at three o’clock in the morning on Sunday when I walked home alone. She and her friend flew home to Brasil. I went to sleep. Both us were sad but hopeful that plans to see each other in April would work out. It was now January 31, and April seemed so far away.

|

| Celebrating the summit Photo by Henry Buckle Loveless |

La Montana

I was nine pitches at 5.10a at the end of the day. They named me Gracias a la Vida after the song made famous by the local Chilean songstress Violeta Parra who grew up near San Fabian and committed suicide in 1967.

PS - Congratulations to Armando and Catalina, who got engaged the weekend after returning from the trip.

|

| Happy Days |

4 comments:

Gorgeous pictures, Greg. What kind of camera are you using?

Thanks Ray,

I have a simple Canon PAS. Not all the pics are by me. Those not by me were either taken by a nice digital 35mm (not sure which kind) or a simple PAS (ditto).

Awesome blog! I am headed down to visit relatives near Rio De Janeiro in May, I think maybe I'll try to make a trip down to Anhangava!

No problem, Max. Give me a shout when you're down here. Anhangava is a bit of a ways south of Rio (I've heard Rio has much better climbing), so it may not be worth the trip, but if you come then let me know.

Post a Comment